Last November, Chinese artist Heimi succeeded to Zhang Fan as winner of the most important prize in the Golden Pinwheel Young Illustrators Competition—the Grand Award, a double prize given to the best foreign and Chinese artists in competition. In a few weeks time, our winner will enjoy her reward and fly to Italy to attend the next Bologna Children’s Book Fair. From 1 to 4 April, Heimi will be part of this annual celebration where all the world’s most celebrated members of the world’s publishing industry meet up.

In spite of her young age—Heimi was born in 1989 in the Southern province of Guangdong—Hei Mi’s powerful and intense style has conquered more than one jury around the planet. Her very first picture book Braids won nothing less than a Golden Apple at the 2015 Biennal of Illustration Bratislava (BIB), before becoming one of the best-selling original picture books in China. One year later, the same work was recognised with a Chen Bochui International Children’s Literature Award. Her art has been extensively showed in China with solo exhibitions in Shanghai in Beijing, and 16 of her artworks toured around the world as part of the retrospective exhibition organised in occasion of the BIB’s 50th anniversary.

C (CCBF): Congratulations on winning the 2018 Golden Pinwheel Grand Award. How do you feel?

H (Heimi): I am really happy and thankful to the Golden Pinwheel organisers and jury members. It is a great honour to receive such recognition.

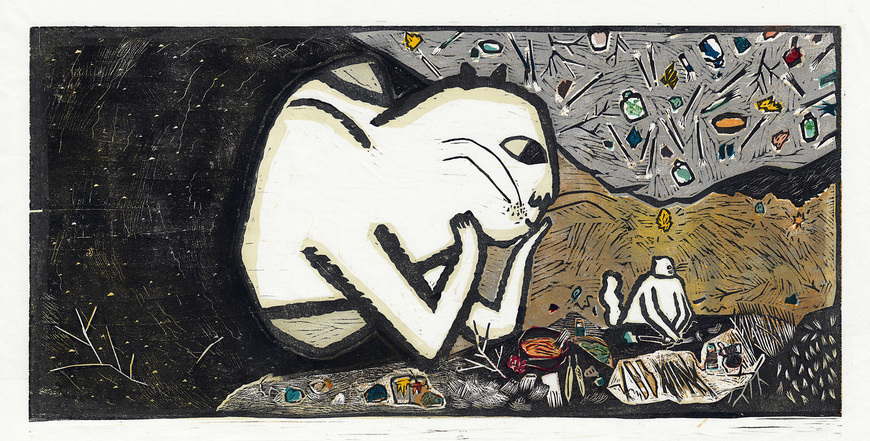

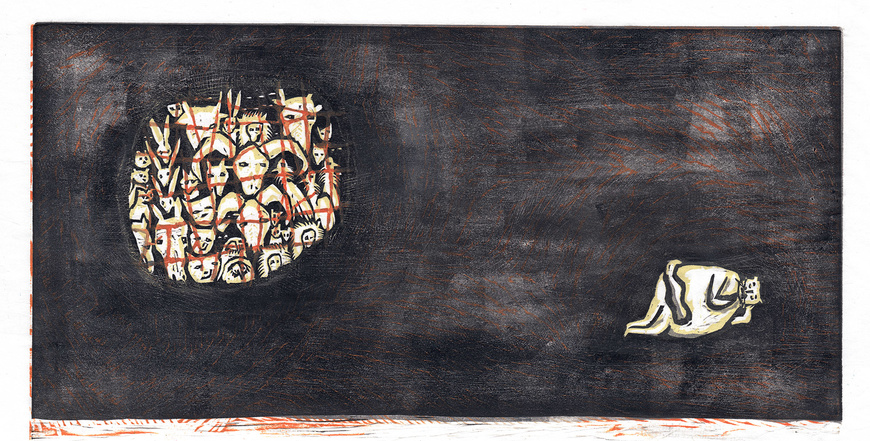

C: Can you tell us more about The Pallas’s Cat Who Wanted Everything?, the work that brought you recognition in the Golden Pinwheel competition? What is the creative process behind it?

H: The story of the pallas’s cat comes from a folk tale brought by Xiong Liang back from a trip in to Qinghai* in 2014. He adapted the story and passed it on to me to illustrate it. This was the first time I was taking a commission, and illustrating someone else’s story was a brand new process compared to working around my own texts.

The story begins like this: “At the beginning of the world, animals had no stripes and patterns. The Pallas' Cat was one of them. He thought his gray fur looked monotonous and dull. But one day he discovered a shining object on the ground—a colourful piece of stone. He liked the colours so much that that he wished he could wear them on his fur. So the pallas’s cat began to look for more coloured stones, maybe he could make pigments out of it…”

When I started exploring the story, Xiong Liang and I talked a lot to decide on the outlines of the story. Xiong Liang was more than the author of the story, he was also a precious guide in all my creative process and gave me a great deal of inspiration. As the story originally came from Qinghai folklore, it took me a long time to feel connected with it. I have to become part of the story before I can express it with pictures but, in this case, the connexion didn’t come to me immediately. One day, a friend gave me a great idea: “The coloured rocks seem to be an important element in your story; you should collect a few rocks and have a good look at them. To express something visually, you need to be able to observe first.” It was a very enlightening piece of advice. Progressively, as I did work around the stones, the pallas’s cat began to take shape in my mind and I got hold of his universe. For me, the narrative frame of the story is just a starting point, I need to expand my understanding of its universe and feed my imagination. Every time I need to make a creative decision on undefined elements of the story, I feel like I am pushed further into it, this is what makes me draw and come up with my own visual interpretation.

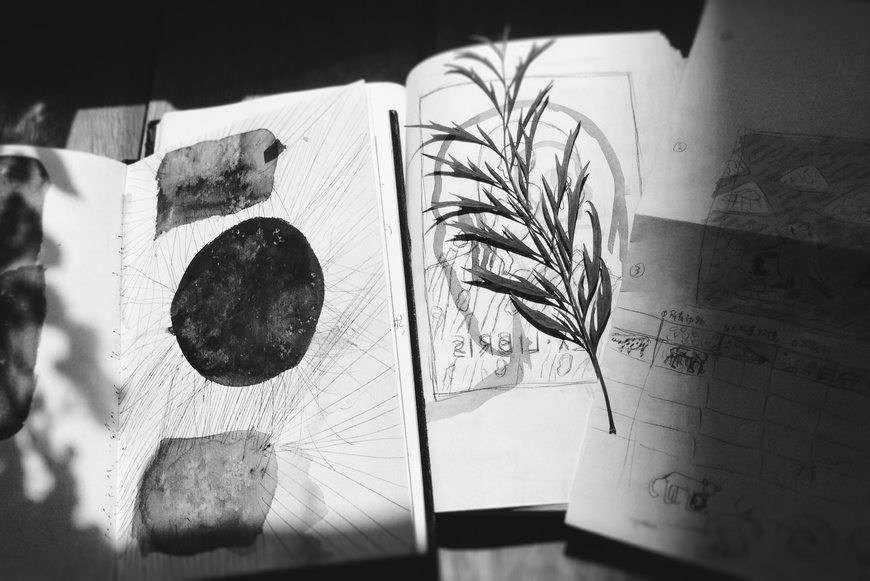

At some point, I experimented with impressionist sketches. I didn’t use any of them in the final drawings but it doesn’t matter, they helped me create a feeling. I tried different techniques, including Chinese ink, water colour, pencil, collage, wood carving etc., in order to find the right style for the story. My final choice was woodcut. Its primitive simplicity echoes with the ancestral times in which the pallas’s cat story develops. We went through quite a few versions to get a first page spread that everyone would be happy with. This first illustration was “The Beginning of the World” which I entered in the competition. This was the very piece that set the tone of the whole project.

(Note*: Qinghai is a mountainous province of Western China, home of a large Tibetan community and well-known for its spectacular natural landscapes)

C: How did you become a professional illustrator?

H: Since I was about 10 years old, I spent most of my weekend and holidays in contact with artists at their studios, either drawing or playing. As I grew up, I learnt painting from Yu Junxian, who is a great water colour master and an artist I deeply respect. Not only did he teach me how to draw, he also gave me many lessons about life in general. As you might expect, I went to an art school–I really had a great time there. After I graduated, I moved to Beijing and joined Xiong Liang’s Ink Collective, where I met many people who would soon become great friends and colleagues. It was a fun, open and earnest atmosphere, which I treasure until today. It is also at the studio that I met Luo Xiting, who worked as an editor at Daylight Publishing House. We are still very close friends, and she is also the editor of Braids (辫子), my first picture book which would mark the very beginning of my professional life as a picture book illustrator.

C: Your works are filled with details taken from ordinary life. How do you balance your creative work and your daily life?

H: I am a keen observer of my environment. I take photos and make sketches to keep records of my observations. I often chose to walk around my neighbourhood or at an open market, as it allows me to relax, empty my mind and connect with my surroundings. Unexpected details will surely catch my eye; you can find them recorded in my observation journal. It could be an old rabbit locked up in a cage at a fruit shop, or a group of wobbly chairs waiting to be recycled. As you randomly take a look at them, you might randomly see something on their scratched old wood--a flaked layer of orange paint, some black blots might suddenly look like the branches of a tree backlit in a bright sunset sky. I, sometimes unconsciously, use random visual fragments like this one in my work.

Therefore field trips are a very important part of my work as an illustrator. I’ll take every opportunity to visit the places where the story takes place. “Being on the set” is completely different from sitting in a studio looking at photos. If a picture book requires a lot of imagination, I try to find objects related to the story. For the pallas’s cat story, I collected natural rocks of all kinds and I used clay to make figurines of the characters. When I draw, all these objects are around me on my desk: they help me immerse in the atmosphere and feel myself as a part of the story.

C: What is the relationship between the illustration and texts to you? What is the most important component of picture book creation?

H: For me, the images and the texts are not interpretations of each other; they’re more like parallel worlds that sometimes cross and complement each other.

My methodology varies whether I am creating my own story or illustrating someone else’s. When I am creating a story of my own, I start with visual impressions. Observations, feelings and thoughts progressively fill my mind like pictures. At the same time, I write down fragments of texts. At a later stage, I put order into the story and let it find the right pace, I also let the images and texts organically grow into each other.

When I illustrate for others, I start with conversations with the author, and as I said earlier, I seize every opportunity to go on field trips and observe as much as possible. Then I review the overall story and start working on the scene that I find most interesting. All the authors I have worked with have been great in that sense–sometimes they even adjusted the texts so that they go harmoniously with the images.

Therefore, it is not about which component—text or pictures—should get more attention, the process is as natural as living one’s life. Of course, no matter who I am creating for, myself or another, I have to be able to take some distance and look at the whole process from afar with an objective eye. It is very helpful to have a big picture and do structural adjustments.

C: Can you share with us your upcoming plans?

H: I have two book projects at the moment. One is a new story for a great writer, the other is a story that I wrote myself about the important people in my life. I look forward to sharing them once they reach maturity. Apart from book illustration, I also created food illustrations with some really interesting collaborators. I was working till very late night looking at food pictures, yum!

I really look forward to more fun collaborations for this new year. Anything unexpected is welcome!

Heimi’s bibliography

Little Tadpole Plays Hide-and-Seek (by Zhong Yu, illustrations by Heimi)

Published in 2014 by Enterprise Management Publishing House (ISBN:978-7-5164-0830-8)

Braids (texts and illustrations by Heimi)

Published in 2015 by Daylight Publishing (ISBN:9787501609147)

The Pallas’s Cat Who Wanted Everything (by Xiong Liang, illustrations by Heimi, dictation by Zha Xi Sang E Kan Bu )

To be published soon by Guomai Culture Media

Heimi’s winning artworks:The Pallas's Cat Who Wanted Everything